[ART in BRANDING] 2. The Industrial Age: Capital Leverages Art

- CBO Editorial

- Jan 5

- 3 min read

Updated: Jan 25

From Florence to the New World

The story of private wealth as a driving force behind art patronage finds its first great exemplar in the Medici family of Florence. As bankers who fully understood art's immense potential, they deployed it masterfully in their quest for power. Through commissioning flattering portraits and financing awe-inspiring public projects, the Medici engineered a remarkable social ascent through clever brand building. Under their rule from 1434 to 1737, Florence transformed into Europe's cultural center.

Their passionate patronage of artists like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Botticelli set a template that would later inspire American industrialists in the New World. And indeed, as we've seen consistently since the beginning of our exploration, art follows capital - so we now turn our attention to the New World, where unprecedented private wealth was being generated on a scale that would reshape not just commerce, but culture itself.

America's New Medici: The Industrial Patrons

The Industrial Revolution brought forth a seismic shift in art patronage. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a period known as the "Gilded Age" or "Age of Industrialists," a new class of patrons emerged. Unlike their predecessors who inherited wealth, figures like Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, Henry Ford, and J.P. Morgan built their fortunes through innovations in industrial infrastructure - the unglamorous but essential sectors of steel, oil, railways, and finance.

These self-made industrialists faced a unique branding challenge. Often derided as "robber barons" for their ruthless business practices, they were in need of measures that were for crafting a more benevolent public image. A pivotal text, Andrew Carnegie's "Gospel of Wealth" (1889), provided the intellectual framework for what later became the template for corporate art patronage and cultural philanthropy. Carnegie argued that the wealthy had a moral obligation to use their surplus means for society's betterment, and that this distribution should be directed by the capitalists themselves rather than the state. The article listed good uses for surplus wealth: libraries, art galleries, hospitals, public parks, music halls, swimming baths, and churches.

The Thirty-Year Cultural Revolution

What followed was remarkable: in just three decades, America witnessed an unprecedented burst of cultural institution-building that would shape public engagement with art well into the 21st century. The Museum of Modern Art, Whitney Museum of American Art, and Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum - institutions familiar to us today - all emerged from this concentrated period of cultural development.

These weren't mere vanity projects. The industrialists, likely studying European history, recognized art's effectiveness in legacy building. Their philanthropic endeavors - establishing universities, libraries, concert halls, and museums - helped rehabilitate their image from "robber barons" to benevolent cultural benefactors.

The Old Masters Strategy

Intriguingly, many industrialists initially focused on collecting European Old Masters rather than art made by their own contemporaries. This preference probably reflected multiple considerations. As "New Money" from decidedly unglamorous industries, they sought connection to refined European traditions. As shrewd businessmen, they recognized Old Masters as proven stores of value. Perhaps most importantly, by acquiring art historically associated with European nobility, they subtly brand-positioned their new industrial power as heir to traditional authority.

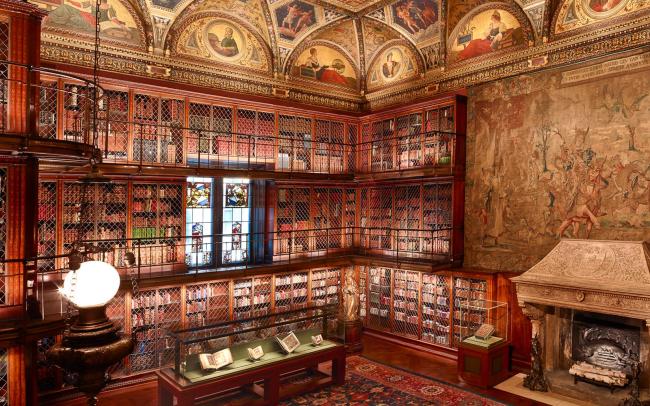

Inside The Morgan Library & Museum, 2. Gutenberg Bible from The Morgan's collection on view, 3. Interior view of The Frick Collection

Breaking from Tradition

Yet just as Henry VIII had once broken from religious iconography to establish a new royal identity, some industrial patrons began forging their own artistic path. Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney established her museum in 1930 to support American artists, while Solomon Guggenheim and his advisor Hilla Rebay championed modern art through their foundation established in 1937. Café Rebay, a cafeteria on the third floor of the Guggenheim Museum New York bears her name.

Photograph by David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, NY

A Legacy of Mutual Evolution

The relationship between patrons and art proved deeply symbiotic. Stable patronage freed artists to focus on their craft, enabling technical innovation and artistic breakthroughs. The need to convey complex ideas through visual means spurred creative development, while large-scale commissions pushed artists to attempt unprecedented challenges. Artists working during periods of territorial expansion encountered diverse cultural influences, enriching their artistic vocabulary.

Indeed, this mutual reinforcement between patron and art continues to shape our understanding of history. Religious institutions, monarchies, and industrial dynasties might be discussed far less today if not for the art, artifacts, and architecture that survived them. Their patronage created not just art, but living history that continues to speak across centuries.

---

This article is part of the ART IN BRANDING series by Seol Park examining the relationship between visual arts and branding throughout history. Our next article will explore how modern corporations have evolved these relationships in the contemporary era.

![[ART in BRANDING] 3. The Corporate Approach: (i) Luxury Wears Art](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/fa1d11_a2565113808a4b4ebe197ed88bb8877d~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_720,h_720,al_c,q_90,enc_avif,quality_auto/fa1d11_a2565113808a4b4ebe197ed88bb8877d~mv2.png)

![[ART in BRANDING] 1. The Church & Monarchy: Art as Tool of Power](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/fa1d11_de6dce115cf94c6fae45669bcf6b6d54~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_720,h_720,al_c,q_90,enc_avif,quality_auto/fa1d11_de6dce115cf94c6fae45669bcf6b6d54~mv2.png)

Comments